One of the great things about golf is the willingness of golfers to help other golfers; even golfers they are competing against. Sam Snead tells the story of being helped by Henry Picard in a way he could never repay. It cost Sam five dollars and fifty cents.

I've been reading Sam's book, The Education of a Golfer. So far, it's been pretty enlightening stuff about Sam's early life and his arrival on tour. Sam was certainly a prodigious driver of the ball, able to drive over 600 yard greens in two, driving 350 yard par four greens, and out-driving pretty well everyone he came across. He also fought a hook in his early days which was more the result of improper equipment than any problem with his technique.

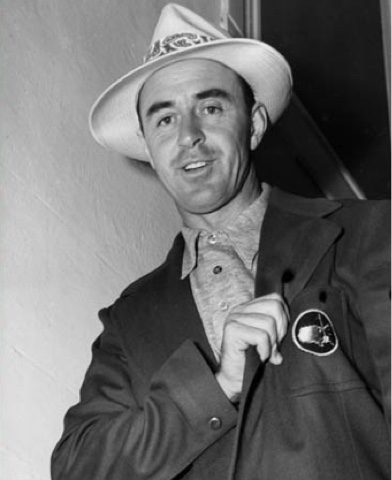

Sam Snead, when he set out on tour, was five feet ten and a half inches tall and one hundred and sixty five pounds. He was not a particularly imposing physical specimen, other than his powerful hands, wrists, and forearms, and his fantastic flexibility, rhythm and balance. When he first arrived on the golf scene he was long, but he could hit some terrible hooks. And, as Lee Trevino liked to say, " a hook won't listen." Sam described his situation as follows:

"In the first place, although I was advertised as 'The Slammer,' driving wasn't the strongest part of my golf game by a long stretch. The pitching wedge was the club I used best. Next came my putting, then my long irons, and after that my ability to play from traps. Driving was the thing I did fifth best... And at times I spray-hooked balls all over the field.

Delivering the long ball is important, but if you can't place it safe from trouble on the fairway and in the best spot to open the green for your second shot, you can't call yourself a pro or even a good amateur."

Sam's driving had got so bad by the winter of 1936 that "Boo-Boo" Bulla, who had made a deal with Sam to share their winnings to try to keep themselves from starving, decided to call off the deal. Then something happened that likely changed golf history. It came in the form of Henry Picard. Sam wrote:

"Just before the firing opened at the Griffith Park course in L.A., Henry Picard walked up and asked, 'How are you hitting, Sam? I hear you are bending them half way to Santa Monica.'

'I'm so wild I've decided to quit the tour and go on home.'

Picard watched me whip out some drives and thought my feet might be the problem. He claimed I was spinning around while in the hitting zone onto my right toe, instead of moving more laterally into the ball on the inside of my right foot. Toning down foot action didn't help.

'Let's look at your driver,' said Henry.

'I'll admit it doesn't feel right,' I said, 'but it worked for me in Virginia and in Florida and I don't like to change it.'

'This stick is too whippy for you,' said Henry. 'Do you remember the photographer who tried to catch your swing at Hershey last fall?'

Thinking back, I remembered that Lambert Martin, one of the top cameramen of the New York World-News, had set up cameras aimed at catching all points of my swing. Martin 'stopped' the action until we came to the point where my descending clubhead was 2 feet from the ball, and then all he got was a blur--even with the camera set at 1/1,250th of a second. Martin said it was the first time he'd been unable to stop a whole hitting sequence. Later they timed my clubhead speed at almost 150 mph.

'Your hands are too fast for such a light and swingy club,' declared Henry. 'I've got an Izett driver that might be the answer for you.'

The Izett felt like a dream the minute I took ahold of it. The first poke took my breath away. The ball travelled an easy 300 yards down the middle. I waved the caddie back further and further, and even when letting out the full shaft, my driving improved about 35 per cent."

Sam asked Picard what he wanted for the driver and Henry told him to just give it a try and they would make a deal if he liked it. Sam, of course, went on a tear with this new driver and would have given Picard "any price" for the club. Henry charged Sam what he paid for it--five dollars and fifty cents. Sam wrote:

"That act of generosity by the Hershey Hurricane could never be repaid, be cause that No. 1 wood was the single greatest discovery I ever made in golf and put me on the road to happy times."

Sam used that driver for three quarters of the 110 victories he had accumulated by 1961, doing whatever he could to hold the club together. Sam wrote: "The exact Wilson Company duplicate of the original which I use today gives results, but in the 1959 Greensboro Open, when I was sniping the ball deep right because of getting my hands too flat, or laid over, at the top of the backswing and then rushing the downswing, I brought the Picard out of retirement. And I played seventy holes without missing a fairway."

Just imagine. Were it not for that driver, who knows where Sam's career might have gone. Five dollars and fifty cents, and the generosity of Henry Picard, turned Sam's game around.